I was obsessed with math proving recently.

Lean is a language you can use to write mathematical proofs. The developers set up a website that turns mathematical proofs into a level-by-level game, letting users learn how to use the Lean language through gameplay.

I first heard about this language around the end of 2024, when Terence Tao mentioned using AI to assist with mathematical proofs, with Lean playing a central role. About half a year ago I came across the game website, but I think I got through the first or second command and then just stopped. Not sure if I was tired that day, or the server went down, or I was busy with something else — whatever it was, I couldn’t make progress and quickly got distracted and gave up.

I learned from friends from my recent Japan trip that cryptographers in Japan are trying to describe the mathematics of cryptography using Lean. So last week I thought of the game again.

This time, once I started it up, I just kept going level by level. I cleared all the natural numbers content built from the Peano axioms.

(Strictly speaking, it’s not a full clear. One level has Fermat’s Last Theorem in it. The level description says the shortest known human proof requires one million lines of Lean code. Actually finishing that one might require going to get a math degree.)

After natural numbers, there are chapters on set theory, real analysis, linear algebra, and more. Right now I’m slowly making my way through set theory.

What does it feel like to write proofs in Lean?

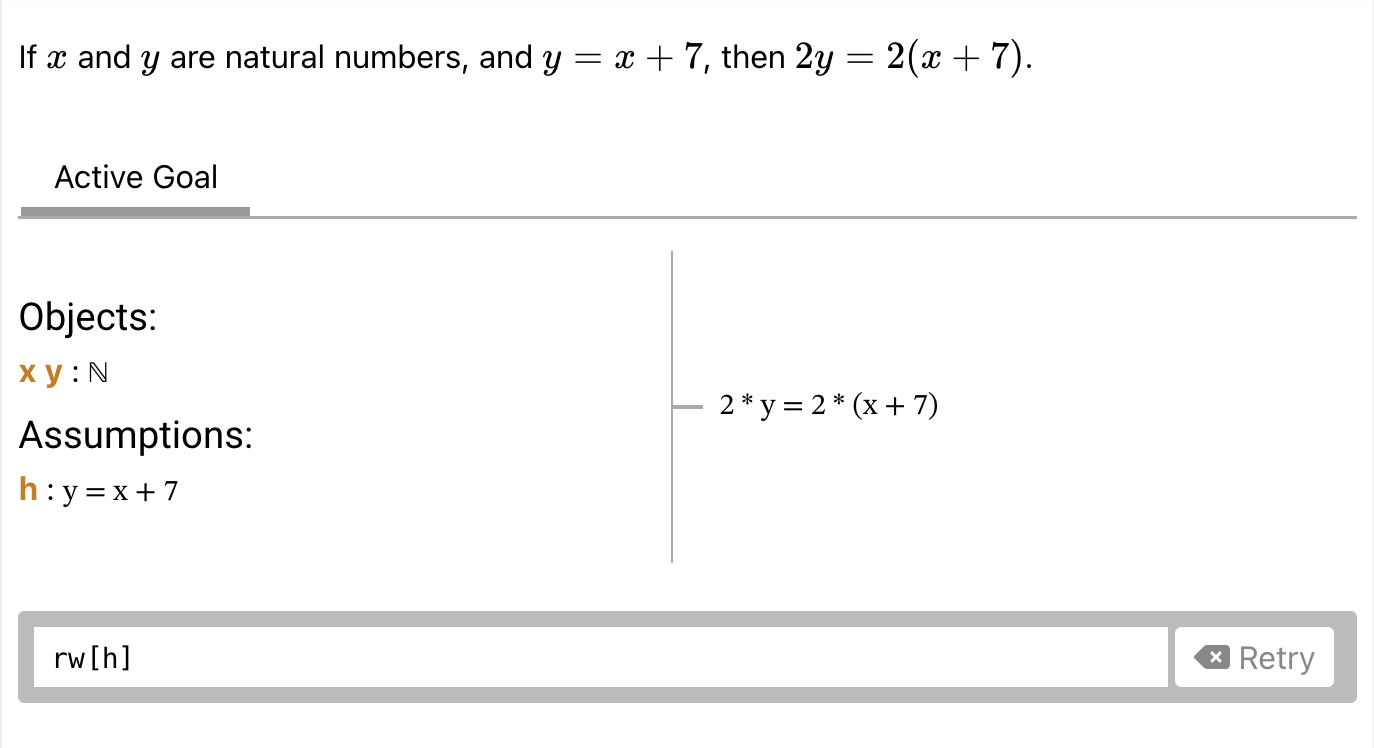

The second level of the tutorial game is a pretty good illustration of what writing a proof in code feels like. The problem in plain language is: “If x and y are natural numbers, and y = x + 7, then 2y = 2(x + 7).”

In the game interface, this problem gets translated into a “goal” and some “hypotheses.”

The goal is to prove:

2 × y = 2 × (x + 7)

And you have certain hypotheses — things that are assumed to be true:

h: y = x + 7

Then the user types rw[h] into the interactive interface. This command says we want to rewrite the expression in the goal by substituting in the existing hypothesis h. Lean understands that this means replacing every occurrence of y with x + 7.

After executing the command, the goal updates to:

2 × (x + 7) = 2 × (x + 7)

When you see that both sides of the equation are identical, you type rfl (short for reflexivity — I didn’t really know what that meant either), and the game interface shows that the proof is complete.

Each time you clear a level, you might unlock new theorems that get added to your toolbox, available to use in future levels.

How has using Lean changed how I feel about math?

I think the mystery of mathematics has disappeared.

Even though I’ve spent a fair amount of my life on mathematics, my training made me a consumer of math, not a producer.

Here’s how I define it: consumers take mathematical formulas and plug in actual numbers to apply them. Producers are responsible for generating the formulas and proving that using them won’t blow up in your face.

Consumers don’t really worry about proofs.

I’d typically encounter mathematical formulas in textbooks or papers, sometimes with a proof attached. But whether handwritten, printed, or beautifully typeset in LaTeX, they’re designed to be digested by a human brain. The reader needs a certain level of mathematical capital to make sense of the formulas and proofs.

Whether a paper is correct gets checked by a group of capable reviewers using their human brains.

For the consumer, math is still magic.

Under Lean, a proof gets broken down into a series of small actions: substituting symbols, applying an already-proven theorem, invoking mathematical induction, using proof by contradiction.

Now when I hear the words “mathematical proof,” my gut reaction is no longer “magic” — it’s “business logic.”

I feel like I’ve seen Adam Smith’s pin factory.

Those pen-and-paper manipulations become computer operations. Verifying mathematical correctness is no longer repetitive human labor — it’s automatic execution by a computer in seconds.

The straight-line conclusion I’m drawing is that everywhere LaTeX currently appears, it will eventually be replaced by something like Lean code.

Why now?

The history of automating mathematical proofs must go back quite a while. I’m only just getting into this, so I don’t know what happened in the past or what challenges had to be overcome to arrive at something like Lean.

I’ve heard the names Isabelle and Coq before. A senior colleague once took a whole team to study Coq in order to develop a better zero-knowledge proof language. All I know is that when they were working through some exercises, only one person on the entire team — the youngest — could solve them. I’m not sure if the language was hard to use or if the exercises were just genuinely difficult.

It’s hard to feel how good or bad a developer experience is without comparing it to other languages and all the hard work behind the scenes. But so far, Lean has been extremely smooth and remarkably intelligent to use. I’ve barely been blocked by any language-specific obstacles.

Thoughts on proof after using Lean

I used to hate mathematical induction most of all when studying math. Beyond telling you a conclusion is true, induction doesn’t really give you any insight. So why spend the brainpower working through a proof? It felt like proving for the sake of proving.

And yet, playing Lean’s game is literally proving for the sake of proving. The number of moves that can actually advance your goal is quite limited — if you can use induction, you use it; if you can breakdown a definition, you break it down.

Let me add a bit about how Lean handles mathematical induction, because it’s actually pretty interesting. When you invoke induction, you specify which variable to apply it to. Lean moves your current goal to a to-do list to be handled later. Your new immediate goal becomes proving the case where n = 0. After n = 0 is proven, your current goal becomes proving the n = k + 1 case, with the “induction hypothesis” introduced as an available assumption. Once both sides are proven, it returns to the original goal.

Experiences getting stuck

In the natural numbers chapters, most problems were about slowly feeling your way through. If a command could do something, you were probably one step closer to finishing the proof. Playing those levels, I barely paid attention to what I was actually proving mathematically.

The problems are usually stated in fairly abstract mathematical terms — like 2 + 2 = 4. In the Peano world, only the concepts of 0 and successor numbers exist. So you first have to decompose 2 and 4 into their successor definitions — 4 is the successor of 3, 3 is the successor of 2. Then you apply the available operations on successors (like how they interact with addition) to complete the proof.

So the brainless strategy is: see an abstract symbol, find its definition and break it down. Keep breaking until you can’t anymore, then figure out how to reassemble.

Some levels require more strategy. In the set theory chapters, some proofs require you to prove that some variable exists which satisfies certain conditions. In Lean, that means producing a concrete example and checking whether it passes those conditions.

For the player, picking the right example sends you to heaven. Picking the wrong one means no matter how hard you try, the proof won’t go through.

This is when you actually need some understanding of the mathematical problem to pick the right example.

The natural numbers world was a two-day binge, but the set theory world had levels where I was stuck for a full day.

For those stuck-for-a-day moments, I’d already snuck a peek at AI, then looked at discussions on the official Zulip forum, and had to work things out by hand before I finally understood. That handwriting step was what it took to understand what a certain symbol meant in terms of proof strategy — and only then could I judge whether the AI was making things up, and what the spoiler hints on the forum were actually pointing at.