I used to experience that kind of development workflow where “the model writes some code, the developer takes a look, and decides whether to accept it.”

A few months have passed, and now the trend is to give the model a task. The model creates its own task list and quietly completes the work by itself.

Models don’t talk back or throw tantrums. But they also won’t complain when they see problems. Whatever instructions come from above, they just execute directly.

Office workers receive monthly salaries, lawyers charge hourly rates—which category should models fall into? Indeed, the companies behind them charge their users monthly fees, so perhaps they’re more like office workers? Models consume tokens when reading and writing text, so maybe they’re more like writers paid by the word?

Once the tokens are exhausted, the model will lie flat and go on strike, asking developers to come back after several hours. If you need them to work immediately, no problem—just increase the monthly salary tenfold (I’m currently using the $20/month plan).

But compared to real developers, even though models count by the word, the amount of text they can process is still vastly greater. Therefore, the entire development mindset needs to change.

Before using Claude Code—the vibe-coding model service I currently use—I held the following beliefs: I’m a senior engineer; I will examine every line of code the model produces; I will understand the operating principles of the entire program; I will insist on clean, maintainable code quality.

After the model completed its first assigned task and generated several hundred lines of code, I instantly abandoned all these principles.

Mainly because the code runs fairly smoothly, and the functionality appears normal. There are no obvious security concerns. When a model can instantly vomit out hundreds of lines of code, is it necessary for me to check whether the code it writes is elegant or maintainable?

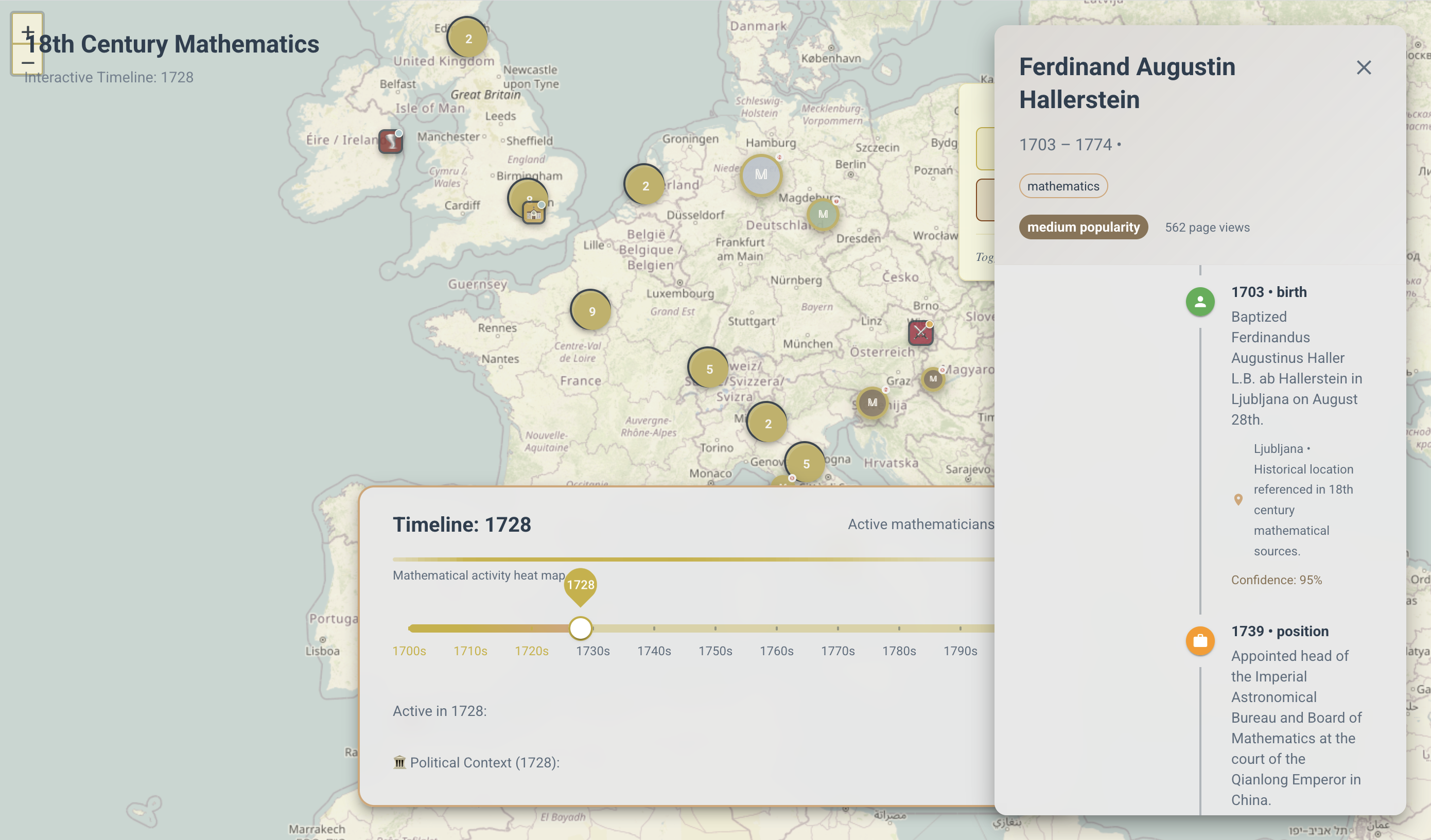

Of course, this is somewhat related to the nature of the project I want to work on. This is a personal leisure project—I want to create a world map marking life events of scientists at different points in time, along with the political environment of those times. Through this project, when reading stories about scientists, one can better grasp the historical context behind them. To reduce the project’s scope, I’ve limited the time period and number of people to 18th-century mathematicians.

This is a harmless project. If it were a more serious project involving more rights or interests, would I have a different development attitude?

During the development process, I first discussed various requirements and features using Claude’s web version and produced a specification document. Then I gave the specification to Claude Code for implementation.

After several rounds of interaction with Claude Code, the model tells the user it needs to clear its memory. At this point, it won’t remember anything previously discussed. After the model restarts, the context needs to be re-established. It told me to create a Claude.md text file where it would record the project overview and current progress. Next time after it loses its memory, it can read this file to get back on track.

Indeed, after using vibe coding, developers become more like product managers, able to focus their energy on what features to develop. Those tedious tasks like how to abstract functions and what to name variables no longer occupy the developer’s time.

The scientist map project requires scraping and organizing Wikipedia data. This reminds me of the joy of data processing. I’ve avoided touching data for a while in my career because data processing is often a high-effort, low-value task—doing it is essentially dereliction of duty. But in the era of language models, at least the cost of writing code has decreased.

I’m reminded of “What Remains: Coming to Terms with Civil War in 19th Century China,” a book about the Taiping Rebellion period. That era had an organization that’s hard for us to understand now, called the “Cherish Character Society” (惜字會). They believed that written characters were precious. Paper with writing on it couldn’t be used for mundane purposes like padding. Characters also couldn’t be written on items like shoes for decoration. Members of the Cherish Character Society would collect things with writing on them.

We can’t understand the Cherish Character Society now because text is too easily obtained—within seconds, we can summon many characters from an input method, and then delete them all within seconds.

The emergence of vibe-coding makes people who manually write software look like members of the Cherish Character Society. Software engineers’ time is expensive, and everything they write requires effort. Therefore, for software engineers to produce text, there must be an important purpose. The text produced, due to its expensive production cost, shouldn’t be casually discarded. The addition and deletion of text must be properly treasured using version control software.

Perhaps characters become the focus only because they’re visible. What people truly expend their mental energy on has perhaps always been clarifying requirements and trial and error. Version control software won’t disappear because of vibe-coding; what’s being managed isn’t text but versions. Developers might feel that the previous version with small flower patterns on the webpage looked better and want to roll back the current work.