We thank Yahsin Huang for the review and helpful feedback

It’s that time again. This post is a bit overdue - my review of the books I read in 2024.

Some of these reviews are quick braindumps from memory, while others come from notes I took after reading, translated to English with GPT’s help. I’ve used GPT to polish the writing flow, though it can’t fix my messy thoughts. As I wrote more, I cared less about perfection. Consider this post as both a GPT-assisted output and a prompt for your own inspiration. While I’ve made my best effort to be accurate, there may be factual mistakes. I welcome feedback and discussions in DM, and I’ll do my best to respond, though I can’t guarantee timely replies.

Books I read in 2024

The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet

I recall when a Korean CEO was interviewed by crypto media about his take on new US regulations. His response - “I’m not American” - drew laughs on crypto Twitter. The question seemed ridiculous at the time: why would a Korean team building decentralized software care about US regulations?

This book changed my mind. To some extent, US regulations have shaped today’s Internet world.

The author, Jeff Kosseff, focuses on just one tiny section: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. The law was enacted in the 1990s, when the entire internet had only three major providers: CompuServe, Prodigy, and America Online.

Section 230 essentially states “The platform is not liable for content posted on it.” This gives powerful protections to today’s Internet platforms. To illustrate this argument, the author provides a compelling example: Twitter processes 6,000 tweets per second, while Facebook handles 3 million posts per minute. How many of these posts could make these companies legally liable? Without Section 230’s robust protection, these companies couldn’t thrive. Consider the contrasting case of Delfi, Estonia’s largest website. Despite having strict content controls, in 2006 some offensive comments appeared on their platform. Even though they were deleted immediately, Delfi was sued and fined - the court ruled they hadn’t protected users sufficiently. The same case in the US would never have made it to court, thanks to Section 230.

The book traces Section 230’s evolution from an overlooked provision to a cornerstone of internet law. After a daring lawyer first utilized it in court, it became so powerful that all Internet platforms came to rely on it. However, this power has been abused by bad actors. Cases escalated from pranks and defamation to serious harms affecting reputation, safety, and life. Yet courts consistently ruled in favor of platforms, even when plaintiffs were powerful White House figures.

The author acknowledges the difficulty in weighing Section 230’s benefits against its harms. While the documented harms are concerning, the protection has enabled public goods like Wikipedia. After examining the most extreme harm cases, the author concludes that Section 230’s protection should remain, with only minor modifications needed. The author’s optimism about platform owners’ self-regulation seems naive to me. Interestingly, in “Power and Progress,” Daron Acemoglu advocates for Section 230’s complete removal.

What lessons can we draw from Section 230’s story for the decentralized systems we’re building?

First, we must recognize that the US legal landscape matters significantly. After all, we wouldn’t be using modern cryptography today if we had lost the Crypto Wars.

The book also prompts reflection on the harms our systems have caused and might cause in the future. Blockchain and cryptography are powerful technologies, and we’ve seen plenty of bad actors abuse these tools. The system faces both externalities and alignment problems that need solving.

Good Economics for Hard Times

This content-dense 300-page book covers all the important topics like immigration, world trade, economic growth, global warming, automation, and universal basic income (UBI). It was finished in Q1 2019, before COVID and ChatGPT would emerge to dramatically reshape discussions around remote work and automation.

Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo have become my favorite economists. I’ve been a fan since their previous book “Poor Economics.”

One quick highlight concerns government “transparency.” As open-source advocates, we strongly value transparency. Public scrutiny helps fight corruption in many cases. But it doesn’t come free - transparency can force government officials to focus on checking boxes to avoid trouble, sometimes creating bureaucracies and inefficiencies.

The book illustrates this point with the Italian government organization Consip. Consip helps government purchase items and was set up after a series of corruption scandals. After Consip’s establishment, government departments could purchase items themselves or via Consip. However, when the Consip option was available, officials always chose it - even when direct purchasing would have been cheaper.

Another highlight is their take on UBI. The authors support the idea, proposing to replace all welfare programs with UBI to reduce administrative costs and bureaucratic friction. The ideal UBI amount would need additional funding, which they suggest raising through taxes on wealth and capital.

Interestingly, in “Power and Progress,” the authors take an opposing view on UBI, seeing it as a narrative crafted by powerful interests (sorry, WorldCoin). However, they agree on taxing wealth and capital to redirect technological development.

Overall, the book demonstrates how randomized controlled trials (RCT) can be a powerful tool for evaluating policy effects - something I’d like to explore further.

The book also made me think about priorities. What issues do people and world leaders care about most? Comparing these to d/acc concerns like nuclear, AI, or bio risks, we see a contrast between the world of “averages” and existential risks (X-risks) - the world of “rare” events.

There’s a saying that the world is getting weirder than before, and past experience offers less valuable guidance for the future. Does this mean we should focus more on X-risks rather than average cases? Or do X-risks matter less because even if we survive them, we still face the everyday challenges of a post-crisis world?

Growth: A History and a Reckoning

I have a separate post on this book, but unfortunately it’s in Chinese.

I like this book’s approach to the topic, blending economic and futurist perspectives.

The book argues against degrowthers and longtermists for their lack of imagination.

There’s no such thing as “the limited resources can’t support unlimited growth.” There are infinite ways we can combine resources for better use. So ideas and research matter.

I see the parallelism that Growth is the north star thinking and GDP is that metric that people are obsessed with.

Growth is not just about forward or backward, it’s about the direction. And if we can decide the direction, there’s a moral problem of the tradeoff of growth.

Moral problems aside, how can we get more growth?

The book argues to increase the production of ideas. The patent system is too old and needs reform. More R&D investment. More people becoming inventors. More efficiency in research. The last one is important. Colleges have too many administrative staff - 50% in Harvard. 40% of researchers’ time is spent applying for grants.

To improve research efficiency, AI must be used. Protein folding is a problem that would consume an entire PhD career to solve one fold. But DeepMind completed millions in one go.

The more interesting part is what are not efficient ways for growth?

Physical infrastructure, bridges, and roads. Big infrastructure projects are super wasteful (as we’ll see in “How Big Things Get Done”). This also falls into the trap of capital-dominated thinking. The diminishing marginal utility of capital will kick in.

Better utilization of land and better cities. Paul Romer is a big fan of cities. He thinks clustering talents in a big city can improve idea exchange, and thus boost economic growth. The author is skeptical about this idea. First, there’s no empirical evidence for that. Second, as remote working is popularized, does meeting people IRL matter that much? Having worked in Ethereum for a long time, most of the time we work remote. Sometimes we travel to Devcon or Devconnect to meet people in real life. I’d say there’s a healthy dose of meeting people IRL. The recently popularized half or one-month long “residencies” seems to be a good balance. I also see a similarity in Popup cities and Paul Romer’s chartered cities idea, which “Good Economics for Hard Times” described how it failed spectacularly.

More education. This is the most interesting point to me. Fewer and fewer countries can get more than 90% of people to finish junior high school and more than 50% of people to college. The “century of human capital” is not happening again. Before reading this book, I believed in the potential of education. Maybe we can 2x, 3x, or even 10x our human capability, but can we compete with the 100x productivity like the protein folding AI achieves?

How Big Things Get Done

Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner specialize in studying large-scale, high-cost projects, such as bridges, subways, and nuclear power plants. Delays and budget overruns are commonplace in these projects. But why do they happen, and is there a systematic way to avoid them? These are the questions the authors seek to answer.

Here are some key points that I still remember:

People often only notice that a project has become a disaster once it’s already underway. However, problems usually start as early as the “why initiate this project?” phase, followed by issues during the planning stage, and finally during execution.

The most critical part is to ensure there’s a satisfactory answer to why the project is being initiated. The authors’ favorite example is the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Initially, the local government wanted to renovate an old building into a Guggenheim Museum. Architect Frank Gehry asked why the government wanted to do this. The answer was that they hoped to revitalize local tourism in response to urban decline. After surveying the site, Gehry found that renovating the old building wouldn’t achieve the desired effect, but building a new structure by the riverside would. This led to the creation of the now-famous museum.

Why are projects often initiated for the wrong reasons? The authors, a close associate of Daniel Kahneman (of Thinking, Fast and Slow fame), have differing views on why projects fail. Kahneman attributes it mainly to behavioral biases, but the authors believe “strategic misrepresentation” in politics is the primary factor. Eventually, they agreed both factors contribute: For smaller projects led by individuals, behavioral biases (such as over-optimism about budgets and timelines or action bias) are key. For projects within complex social structures, like governments or large corporations, strategic misrepresentation (underestimating costs or timelines to gain approval) becomes the main culprit.

The authors summarize their philosophy on successful projects with the phrase slow thinking, fast execution. This means preparing thoroughly during the planning stage and acting decisively during execution. While this may sound obvious, it might also seem like a “waterfall” approach to those accustomed to Scrum.

Planning, according to the authors, isn’t about sitting at a desk staring at a blank sheet of paper or creating thick, overly detailed project proposals. Such approaches misunderstand the essence of planning.

The authors view planning as a dynamic process rather than a static one. In the case of the Bilbao museum, Gehry used 3D architectural simulation software to refine design details. Pixar’s high movie success rate comes from thoroughly identifying potential issues during the planning phase. Their directors spend up to two years brainstorming story ideas, create rough hand-drawn storyboards for feedback, and refine their work through multiple iterations before starting animation.

The Latin word experiri is the root of both “experiment” and “experience,” and the authors consider these two to be invaluable to projects. Using simulations or iterative processes, as with Gehry and Pixar, allows exploration of possible scenarios and identification of potential problems before significant investments are made. This aligns with the lean startup’s iterative philosophy.

Regarding experience, the authors highlight three key points:

Avoiding uniqueness bias: Most people think their project is unprecedented. Projects branded as “newest, biggest, first” often start with grandiose but flawed motives, sometimes driven by political or personal ambitions. Leaders may refuse to halt bad projects due to sunk cost bias. Alternatively, project initiators might overlook similarities between their project and others. The result is often underestimating costs and timelines. The author advocates Daniel Kahneman’s lesser-known reference class method, which involves looking at similar projects to see how much they exceeded budgets and timelines. While this doesn’t eliminate risk, it provides insights into potential pitfalls. The authors have built a database of large-scale projects for future reference.

Leveraging expert experience: The author emphasizes hiring top talent from day one instead of waiting until problems arise to bring in “firefighting” experts. Using established models wherever possible can also prevent mistakes, just like avoiding new, untested software packages.

Positive vs. negative learning: Modularization is a standout concept. Solar and wind energy projects tend to have the least cost overruns and delays because they use modular components, allowing incremental progress and learning from each unit. In contrast, nuclear power plants, which require all components to work perfectly before operation, have severe cost overruns and delays. Negative learning occurs when every new issue exacerbates overruns and delays, causing people to hide problems and avoid learning. The authors believe the future of nuclear power lies in smaller, modular designs. Large-scale projects tend to drag out over time, increasing exposure to “black swans” like pandemics, tsunamis, or reactor meltdowns.

From Development to Democracy: The Transformations of Modern Asia

Now we move to the world of institutions.

Dan Slater and Joseph Wong examine the economic and political histories of 12 Asian countries and propose a rather controversial theory.

The traditional view has been that as a country’s economy develops, its people will desire more political participation, eventually leading the nation to become democratic. Traditional view (“Economic origins of Dictatorship and Democracy”, it’s Acemoglu and James Robinson again!) also says the dictator yields to the threat of revolution. This book argues the otherwise, the dictator yields because they look for stability.

However, the real world doesn’t always follow this script. For instance, while Taiwan and South Korea experienced both economic growth and a transition from authoritarianism to democracy, countries like China and Singapore have achieved remarkable economic growth without becoming democracies.

It was also previously believed that when authoritarian governments weaken and collapse, nations naturally transition to democracy.

The authors’ controversial theory argues otherwise: authoritarian governments transform into democracies from a position of strength. They don’t democratize because they are weak and have no choice, nor because of benevolence. Instead, these governments believe they are strong enough to win elections even in a democratic system, ensuring continued stable support while maintaining their privileges and power.

So why don’t strong authoritarian governments simply continue their rule as before? Why transition to democracy at all? Because good times can’t last forever—authoritarian regimes inevitably decline. If they don’t democratize at the most advantageous moment, they will face severe consequences later.

Why can’t good times last? Economic development may grant authoritarian regimes legitimacy, but it also fosters a public that demands more. This is known as the Tocqueville paradox—rising expectations weaken the foundation of the regime’s rule. At this point, ruling elites may turn on each other, resort to violent suppression of opposition, and plunge the nation into prolonged chaos. From this book, I learned the phrase “Après moi, le déluge” (After me, the flood).

The authors call on the international community to refrain from pressuring authoritarian regimes to democratize. Instead of measures that weaken authoritarian regimes, efforts should focus on supporting actions that enhance the foundation of their rule in a way that allows for a stable transition.

The Price of Collapse: The Little Ice Age and the Fall of Ming China

The author, Timothy Brook, argues that the fall of the Ming dynasty was influenced by a series of extreme climatic events. In an agrarian society, people depend on the heavens for their livelihood—plants need ample sunlight and water to grow, providing food for people. However, the Ming dynasty existed during a “Little Ice Age,” marked by cold and dry conditions, with summer rivers freezing over. Insufficient food production led to skyrocketing food and commodity prices, eventually culminating in social collapse, including instances of cannibalism. Based on my experience with games like Timberborn, Frostpunk, dotAGE, and Ratopia, I can roughly grasp the dynamics described.

Traditional economic historians attribute the inflation during the Ming dynasty to the influx of silver. After all, inflation occurs when money outpaces available goods, but whether this was due to an increase in money or a decrease in goods warrants further discussion. Large amounts of silver were mined in Japan, Mexico, and Peru and transported to China via maritime routes to purchase cheap silk, porcelain, and other goods. While this explains the increased money supply, the author believes the effect remains unproven. The only area the author identifies as impacted by silver is the art market, where amateurs drove up the prices of calligraphy, paintings, and other artworks (perhaps similar to modern NFT speculation?). The author ultimately attributes inflation to climate-induced food shortages but avoids elaborating further, preferring to focus on the chapter discussing silver and its intriguing points.

With the formation of maritime trade networks in the South China Sea, various nations had their concerns:

England: Around 1600, England faced an economic downturn. People attributed this to a shortage of currency, reasoning that buyers couldn’t purchase goods without money (a somewhat odd rationale). Why was there a currency shortage? Because the East India Company used much of it to buy overseas goods. As a result, England considered restricting the company’s trade. Responding to this, East India Company director Thomas Mun quickly wrote an essay countering the mainstream view. He articulated the principles of mercantilism, arguing that simply hoarding silver was useless; true wealth came from favorable foreign trade.

Spain: Spain had colonies in the Americas and a stronghold in Manila. Initially, Spain hoped that global wealth would flow back to Madrid. Instead, silver mined in the Americas flowed to Manila to purchase cheap goods produced in China. Concerned, the Spanish royal family raised this issue with the bishops overseeing South American colonies. This prompted the bishops to consider ways to restrict trade between South America and Manila. Merchants in Lima, Peru, quickly defended the importance of South America-Philippines trade, arguing that it enhanced royal wealth.

China: China followed a tributary trade system where foreign envoys presented tribute, and the Ministry of Rites would return gifts more valuable than the tribute. Foreigners felt they profited from this trade, while the Chinese took pride in their perceived superiority. At the time, maritime trade was banned, and private trade with foreigners was a crime.

The author notes that during this period, China lacked rhetoric supporting trade. This wasn’t due to an absence of mercantile concepts but rather because there was no platform to persuade the public. The book explains that societies like Mun’s England and the Lima merchants’ Peru accepted the overlap between private and public interests. In contrast, Confucian thought in China strictly opposed private and public interests. Chinese merchants would hide their opinions and account books, destroying them after transactions to avoid scrutiny from competitors or officials.

What this highlights isn’t the danger of Confucian culture but the importance of healthy spaces for free expression.

Power and Progress

“AI is about to replace humans, and humanity will face mass unemployment, relying solely on Universal Basic Income (UBI) to survive?”

“You can’t stop the progress of technology; someone else will eventually invent it.”

“The harm caused by technology is temporary. People will always invent more technology to solve the disasters created by previous technology.”

In Power and Progress, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson argue that these ideas are all incorrect.

The authors believe that the trajectory of technology can be guided. People can direct technology towards creating more jobs rather than replacing them. They can also guide it to increase workers’ income rather than boosting capital returns.

What evidence supports this claim? The weight of the entire book lies in reviewing the history of humanity’s interaction with technology: from watermills and windmills to steam engines, electricity, computers, and the internet. The choice of how technology is utilized profoundly affects human well-being.

How can the direction of technology be guided? Or how is the trajectory of technology typically shaped?

The first and most important factor is narrative and persuasion. Often, influential and powerful individuals propose dominant narratives, like the three statements mentioned earlier. To guide the trajectory of technology, it is crucial to address these mainstream narratives and promote technology that is human-centered, supportive of people, or beneficial to society. The authors advocate for the development of unions and labor organizations and emphasize the importance of civic actions. They also suggest learning from figures like Audrey Tang (Taiwan’s Digital Minister).

The second critical factor is managing incentives and the flow of resources. When technology develops in harmful directions, harmful industries often accumulate more capital, which is then reinvested in technology, further exacerbating the problem. Solutions include subsidies, taxes, legislation, and other corrective measures, with several strategies recommended by the authors.

It seems Acemoglu is everywhere. He has important opinions on every seemly unrelated topics.

The Chinese Typewriter

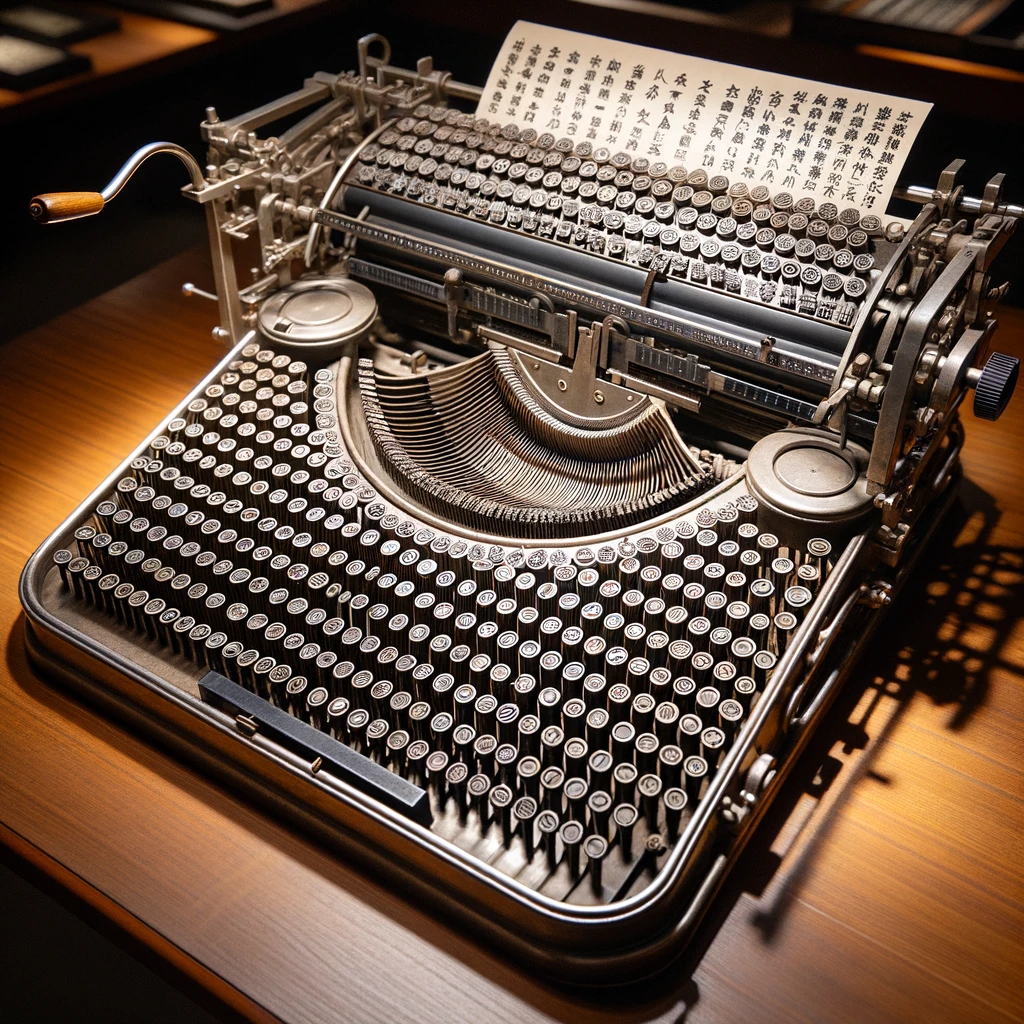

Thomas S. Mullaney traces the history of the Chinese typewriter and tells a story of how culture shapes technology and later how technology shapes culture.

The image of a typewriter has always been shaped by the English typewriter. When people think of a Chinese typewriter, they often fall into the following line of thought:

- A typewriter is a device with keys.

- Each key corresponds to a letter.

- Chinese has no letters; its basic units are characters.

- There are thousands upon thousands of Chinese characters.

- Therefore, a Chinese typewriter must be a massive machine with thousands of keys.

This line of thought became a meme in the West around 1900 and has persisted to this day. If you ask ChatGPT-4 to draw a Chinese typewriter, it might produce an image with the following description:

Here is an image of a traditional Chinese typewriter. This device showcases its unique design, including the dense, organized grid of Chinese character slugs.

Western typewriter manufacturers, such as Remington, always believed they had developed a universal, modern tool, capable of tackling languages as challenging as Thai or Arabic. However, they could not produce a satisfactory solution for Chinese (which includes the now-grouped CJK languages: Chinese, Japanese, and Korean) using their existing models.

The root of the problem was the manufacturers’ imagination being constrained by alphabet-centric language systems. Yet, at the time, both typewriter manufacturers and those attempting to reform Chinese considered the language itself to be backward. They awaited the arrival of a Chinese Cadmus—the mythical Greek figure who introduced letters to humanity. When would these stubborn Chinese finally abandon characters and adopt an alphabetic system?

In 1911, the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty. Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培), the Minister of Education, convened a group of language experts for a three-month conference to standardize the pronunciation of Chinese. Their efforts resulted in the creation of Zhuyin Fuhao (Bopomofo).

This was the moment Western typewriter manufacturers had been waiting for—they rushed to introduce typewriters designed exclusively for Zhuyin. In renowned language reform journals of the time, these machines were advertised with outputs like this:

ㄣㄊㄜㄏㄨㄚㄍㄨㄛㄧㄣㄉㄚㄗㄐㄧ (恩特華國音打字機 Entehua National Phonetic Typewriter)

Unfortunately, these pioneering machines using phonetic scripts never achieved widespread adoption and eventually faded into history.

Am I Normal?: The 200-Year Search for Normal People (and Why They Don’t Exist)

Sarah Chaney argues that the concept of “Normal” emerged after the normal distribution.

Before the 1800s, the concept of “normal” did not exist. “Normal” was merely a mathematical term, meaning perpendicular.

Carl Friedrich Gauss used the bell curve to help astronomers predict planetary orbits.

Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet began applying the bell curve to various social phenomena.

People started fitting distributions of physical traits, like height and weight, into the normal distribution, introducing the distinction between “normal” and “abnormal.” However, these samples often came from white males.

This led to the emergence of the idea of an “l’homme moyenne” or an average person—a notion of what a “normal” person should look like.

Conclusion

I think the main takeaway from 2024 is that technology can be directed, and we should think hard about that. Over the years, I’ve been contributing to blockchain and zero-knowledge proofs. They are very powerful technologies, and they will impact society. So far, I feel the majority in the ecosystem is still trapped in the imagination of the Web2 world. Scaling and adoption have been prioritized too much. I feel this would repeat the same mistakes as Web2 in the past. The lack of humanity discourse worries me. Developing some competency and opinions in social science is something I would like to do in 2025.